At the end of April, the official number of covid deaths in Brazil surpassed 400,000. Measured by the number of inhabitants, no country in the Americas has seen more people die from infection with the coronavirus. But it is not only this number that is shocking. Meanwhile, the social impact of the Bolsonaro government’s failed pandemic policy is also becoming increasingly clear.

“Hunger is back,” recent studies note. The crisis threatens to undo the successful fight against hunger and absolute poverty between 2003 and 2013. And yet Brazil is the world’s third-largest food exporter.

Food as a human right – The Força Tururu collective collects and distributes food donations (Photo: Coletivo Força Tururu)

Food as a human right – The Força Tururu collective collects and distributes food donations (Photo: Coletivo Força Tururu)

Brazil had experienced a success story: In 2014, the proportion of Brazilians suffering from hunger fell to less than five percent and the country disappeared from the United Nations’ world hunger map for the first time. For the far-right president Jair Bolsonaro, this was already reason enough in an interview with El País in 2019 to declare the statement that people in Brazil still suffer from hunger to be a “lie” and “populist talk.“

But whether the president wants to admit it or not, the country is far from having solved the problem of hunger. Brazil was already rapidly moving back onto the world hunger map in 2019. According to the Nationwide Household Sample Survey (PNAD, comparable to the German microcensus), the percentage of households with food insecurity increased by 63 percent between 2013 and 2018. In absolute terms, this means that by the beginning of 2018, some 85 million Brazilians were already worried about their future access to food, it was already limited, or they were going hungry – a shocking record since data collection began in 2004.

Food insecurity is growing due to the Corona pandemic and failed government policies

As two recent studies by the Penssan network and the Food for Justice research collective at Freie Universität Berlin show, the pandemic has contributed to a further deterioration of the food situation. Nearly 117 million Brazilians were food insecure by the end of 2020. 19 million of them were already suffering from hunger; almost twice as many as in 2018, when there were ten million.

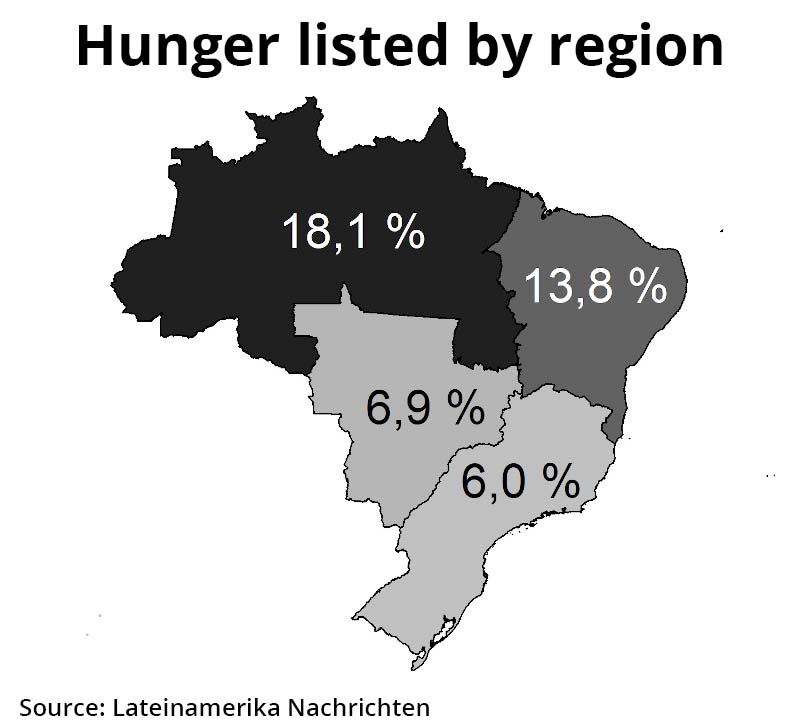

This development affects certain groups more than others. People who live in rural areas in the north or northeast, who have small children, who are the sole provider of family income as a woman, or who are black have considerably less secure access to food. In the north, almost one-fifth of the population is already affected by hunger; in the northeast, one-seventh. Cidicleiton Zumba, whom LN interviewed early in the pandemic (see LN 550), also confirms this deterioration. He lives in Tururu, a precarious neighborhood on the outskirts of Recife. “We now see very many families going door to door in Tururu asking for food. We as a collective also receive a lot of requests for help. It especially affects people who live on the streets. And since the beginning of the pandemic, more and more people are slipping into poverty,” Zumba said.

The “fight against hunger” was one of the most important campaign promises of Luis Inácio Lula da Silva’s presidential campaign. In his inaugural speech in 2003, he proclaimed, “If, at the end of my term, all Brazilians can eat a meal three times a day, then I will have fulfilled the mission of my presidency.” In just his first 30 days, his government launched the “Zero Hunger” program, and between 2004 and 2013, the number of hungry people halved to 7.2 million.

#TemGenteComFome – Civil society is collecting donations (Photo: Coletivo Força Tururu)

#TemGenteComFome – Civil society is collecting donations (Photo: Coletivo Força Tururu)

#TemGenteComFome – Civil society is collecting donations (Photo: Coletivo Força Tururu)

The fact that the food situation has improved under the government programs of the PT Workers’ Party has been recognized internationally. The FAO particularly highlights the introduction of school lunches – usually a hot lunch of beans, rice and vegetables for 43 million children and young people. The food used for these meals was largely purchased from local, smallholder agriculture through the PAA program, which also contributed to poverty relief.

The first setback for this successful policy against poverty and hunger came in 2014. International prices for raw materials, whose export had previously formed the financial basis of PT’s social policy, had already fallen since 2012. This was followed by a significant economic slump. With the parliamentary coup against President Dilma Rousseff and the assumption of office by Michel Temer in 2016 (see LN 507/508), the dismantling of social policy began. Particularly fatal in this context is the law restricting state spending, which was passed in December 2016. It limits the state budget for 20 years in principle to the 2016 level (plus inflation) – despite a growing population. So even if the political will were there for higher social spending, the law significantly limits the government’s room for maneuver in the pandemic.

In sharp contrast to Lula, Bolsonaro suspended the activities of the National Council for Food Security (Consea) on the very day of his inauguration. Until then, Consea, created in 1993, coordinated federal food security programs and played an important role in the fight against hunger, including dialogue with civil society. In September 2019, the Brazilian Parliament voted to abolish the Council, and most employees of the Food Security Secretariat were dismissed.

Instead of “zero hunger,” “zero planning against hunger” was now government policy. This is also evident in the dissolution of government food reserves and the erosion of the PAA agricultural program. In the first nine months of the pandemic – with all its restrictions on trade and transportation – the government spent only seven percent of PAA’s 500 million budget. Plans already approved by Congress and the Senate to increase payments to smallholder agriculture as part of the emergency aid were vetoed by Bolsonaro in September 2020. “But it is precisely these family farms that provide food for the population,” Ana Maria Segall, a researcher on food security, tells LN.

Despite 19 million Brazilians going hungry, Bolsonaro boasted at the UN General Assembly in September 2020 that his country had never exported so much and that the world was “increasingly dependent on Brazil for food.” In fact, Brazil is the world’s third-largest food exporter – after the U.S. and China. In 2019, the country exported 240 million tons of sugar, soybeans, corn, orange juice, beef and others to 180 countries, generating $34.1 billion in sales. For the current year, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IGBE) also predicts a record harvest of cereals, vegetables and oil crops. What seems paradoxical is, for Segall, a matter of prioritization: “While agribusiness receives government incentives, family farms are left empty-handed. Instead of a paradox, we’re seeing a lot more policy decisions about what the government finds important and supports.”

The cultivation of soy and corn, which is lucrative for export, has been expanded more and more in recent years – at the expense of staple foods such as beans and rice. The devaluation of the real also means higher profits are being made by selling abroad. Between March and July 2020 alone, rice exports increased 260 percent. More expensive imports and hoarding during the pandemic led to an average 14 percent increase in food prices last year: Instead of 15 reais, for example, a five-kilo bag of rice suddenly cost 40 reais (the equivalent of about ten euros in 2020).

Despite this, the monthly emergency aid paid out during the pandemic, initially 600 reais, was successively reduced and finally suspended completely between January and March 2021.

As the Food for Justice study shows, it played a fundamental role last year: “Emergency aid reached those most in need. Without it, the situation would be even worse. However, the amount is not enough to maintain a certain level of food security, which depends very much on income,” explains Renata Motta, professor at the FU Berlin and part of the researchers inside collective in an interview with LN. As of April, emergency aid was resumed at an average of 250 reais (38 euros) per family – completely inadequate, as Segall also finds: “Emergency aid is only accessible to a limited number of people and its value is only a quarter of what was paid out in mid-2020. The population is exposed to hunger and the pandemic without government support.”

Eliane Farias do Nascimento from the Santa Luiza favela in Recife also confirms this assessment to LN: “There is a lot of hunger in the neighborhood, many have become unemployed. The aid they pay is far too little. It’s only enough for food or for drinking water or for electricity. It is difficult to survive and at least have bread in the house. Two of my children still drink milk, but some days I can’t buy any.”

Faced with increasing hunger and government inaction, civil society is organizing to mobilize donations. “Tem gente com fome” (There are people who are hungry) is the name of one of the campaigns joined by smaller and larger organizations such as Amnesty International, Oxfam Brasil and Instituto Ethos.

The landless movement MST regularly donates large quantities of food grown on agrarian reform land by its members. Most recently, they distributed 100 tons of food and 3,000 liters of milk in various regions of Brazil at the end of April. But smaller organizations also see campaigning as the order of the day. For example, after twelve years of cultural activism, the Força Tururu collective first asked for food donations in the neighborhood in 2020 and continues to do so today in the face of need. “We respond to the suffering of our neighbors, at the same time they see that we demand food as a human right” says Cidicleiton Zumba. “Admitting that you are hungry is not easy for anyone, it is still a taboo. But with us they can talk about it. And I am happy that we are succeeding in breaking this taboo.”